Few biblical texts have been as frequently invoked in Catholic moral teaching on homosexuality as Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13. For centuries, these verses have been interpreted as absolute and universal prohibitions of male-male sexual relations, often treated as self-evident expressions of divine law. Despite their historical prominence, however, the contemporary Magisterium has largely passed over them in silence, omitting them from nearly all its major doctrinal statements on homosexuality over the past fifty years—even the Catechism.

This omission suggests an underlying tension in the Church’s moral reasoning. On the one hand, traditional Catholic sexual ethics have long relied on Leviticus to justify the claim that homosexual acts are “intrinsically disordered.” On the other hand, modern biblical scholarship has increasingly challenged the assumption that Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 articulate an unchanging moral law rather than culturally specific purity regulations.

This growing disconnect between the findings of historical-critical exegesis and the Church’s doctrinal foundations demands a rigorous reexamination of these texts. This study will undertake a comprehensive exegetical and historical analysis of Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13, examining their linguistic, cultural, and theological contexts to determine what they originally prohibited—and whether that prohibition remains relevant for contemporary moral theology.

First, we will analyze the Hebrew text, considering key linguistic ambiguities that complicate traditional interpretations.

Second, we will situate these verses within their broader ancient Near Eastern and Israelite legal frameworks, exploring whether they reflect universal moral principles or culturally contingent concerns.

Third, we will trace the history of interpretation from Jewish rabbinic traditions to medieval Christian theology, highlighting how these verses have been expanded, recontextualized, and selectively applied over time.

Finally, we will consider how the Catholic Magisterium has engaged (or failed to engage) with these texts in recent years, questioning what role, if any, they might play in the Church’s moral teaching on homosexuality today.

As always here at Deconstructing Cleric, this study does not seek to undermine Catholic moral theology but to engage it with intellectual honesty and theological depth. If the Church’s teaching on sexual ethics is to be coherent and credible, it must be grounded in a historically sound and exegetically rigorous interpretation of Scripture. This inquiry, then, is not about using “isolated phrases for facile theological argument”1 but about safeguarding the integrity of Catholic moral reasoning itself.

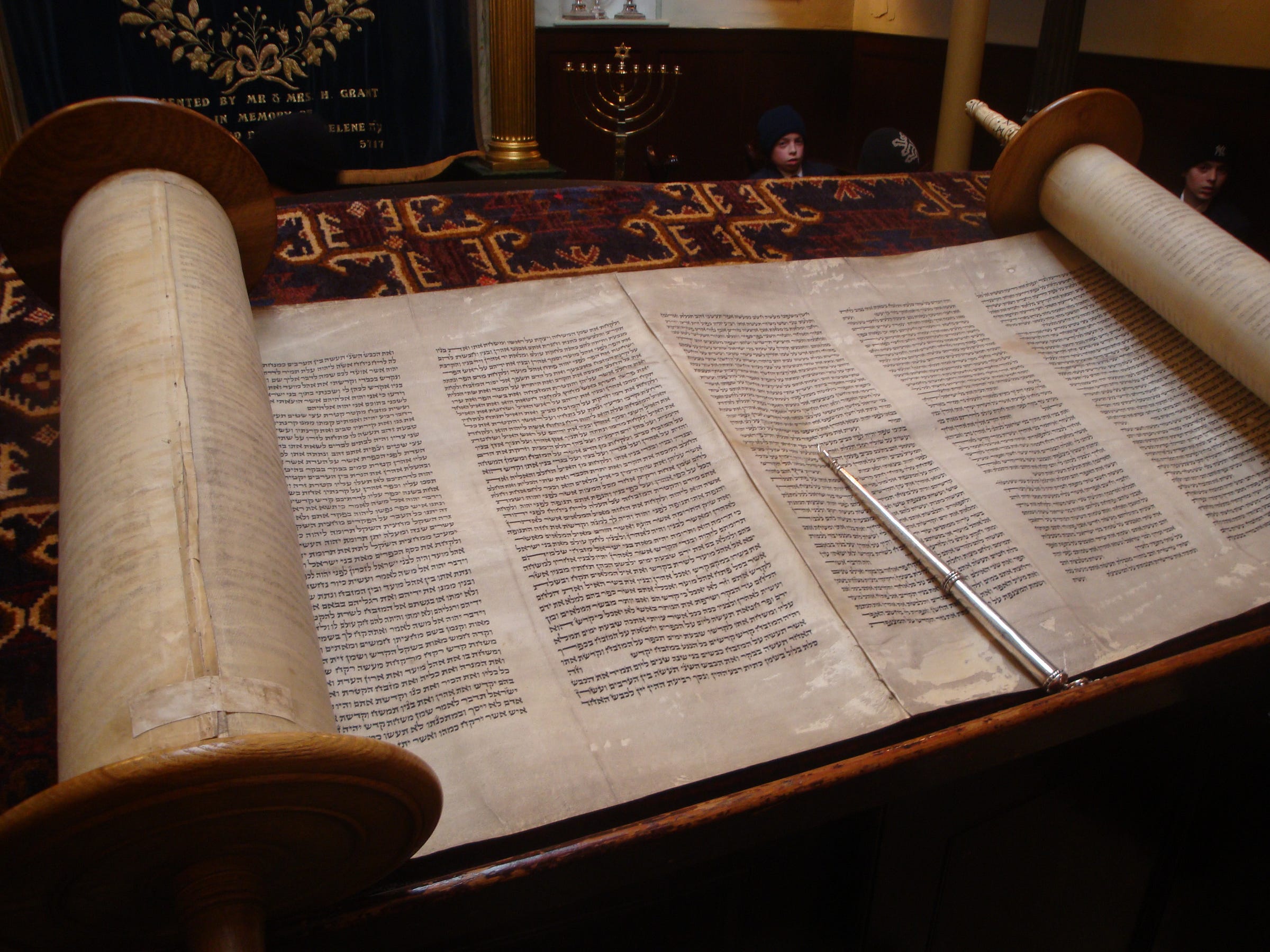

The Text in Context: What Do Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 Actually Say?

Interpreting Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 requires careful attention to both the Hebrew text and its literary and historical context. While most English translations render these verses as straightforward prohibitions of male-male sexual relations, the original text presents several linguistic ambiguities that complicate this reading.

Interpretations of Mishkevei Ishah

Leviticus 18:22 states: “We’et zakar lo tishkav mishkevei ishah to‘evah hi”—literally, “And with a male you shall not lie the lyings of a woman; it is an abomination.”

Leviticus 20:13 expands this prohibition to include a penalty: “We’ish asher yishkav et-zakar mishkevei ishah to‘evah asu shenehem mot yumatu demehem bam”—“And a man who lies with a male the lyings of a woman, both of them have committed an abomination; they shall surely be put to death, their blood is upon them.”

At the center of both verses is the key phrase mishkevei ishah (משכבי אישה), commonly translated “as with a woman” or some equivalent phrase.2 However, scholars of the Hebrew Bible such as Saul Olyan, professor of ancient and Judaic Studies at Brown University, suggest that this phrase is not self-evident in meaning and requires careful philological analysis.3

For one thing, mishkevei ishah appears nowhere else in the Hebrew Bible than these two verses, making it a unique idiom whose precise meaning must be inferred from context. Olyan identifies a closely related phrase, mishkab zakar (משכב זכר), meaning “the lying down of a male”, which occurs in Numbers 31:17-18, 35 and Judges 21:11-12. In these passages, mishkab zakar is clearly a euphemism for male vaginal intercourse, as virgin girls are described as those who have “not known mishkab zakar.” By analogy, then, if mishkab zakar denotes the active, male role in male-female intercourse, mishkevei ishah likely denotes the receptive, female role.

Furthermore, Olyan notes that wherever the verb shakav (שכב, “to lie with”) appears in a legal context in the Hebrew Bible, it always addresses the active, male partner, who is commanded not to “lie with” various receptive, female partners (cf. Lev 19:20; 20:11, 12, 18, 20). Thus, when Leviticus 18:22 states, “With a male you shall not lie mishkevei ishah,” it would seem to specifically forbid a male from assuming the active role in male-male intercourse.

Leviticus 20:13, however, seems to expand the prohibition by shifting from the singular to the plural. The first clause of this verse refers to “a man who lies” (ish asher yishkav—singular), but the second clause states that “both of them have committed an abomination”(to‘evah asu shenehem—plural). Olyan suggests this may indicate a later redaction, expanding the original law condemning only the active partner to include the receptive partner as well. We shall examine why this expansion may have occurred in a later section of this analysis.

The Use of Zakar

English theologian James Alison highlights another potentially significant lexical choice in Leviticus 18:22. The text does not prohibit a man (ish, אִישׁ) from lying with another man (ish), but instead prohibits a man from lying with a male (zakar, זָכָר).

This is not a trivial distinction. In biblical Hebrew, ish refers to a man, that is, a socially recognized adult male, whereas zakar is a more general term that refers simply to a biologically male being, regardless of age or social status.4 The word zakar is commonly used when referring to males in ritual or cultic contexts, such as laws concerning circumcision, sacrifices, and priesthood requirements (cf. Lev 1:3, Exod 12:5). It can also refer to males in contrast to females (cf. Gen. 1:27), or to young boys rather than adult men (cf. Exod 13:15).

Alison suggests that this unusual choice may indicate that the prohibition of Leviticus 18:22 is not aimed simply at adult men “lying with” other adult men of equal status (in which case the word ish would have been better employed), but rather at men lying with specific categories of males—perhaps younger males or dependents.5 This interpretation is not without historical precedent. For example, Martin Luther’s 1534 German translation of the Bible translates zakar in both Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 as Knaben, meaning “boy” or “youth,” implying that this law was a prohibition on pederasty rather than all male-male relations.6

The Absence of Kemo

Another keen observation by Alison concerns what the Hebrew text does not say. As we have seen, most English translations render Leviticus 18:22 as follows: “You shall not lie with a male as with a woman.” However, such translations insert the word “as” (kemo, כְּמוֹ), which does not actually appear in the Hebrew text.

In biblical Hebrew, kemo is the standard word for “as” or “like,” used when making comparisons between two things.7 For example:

Psalm 1:3 – “He is like (kemo) a tree planted by streams of water.”

Exodus 15:5 – “The deep covered them; they went down into the depths like (kemo) a stone.”

If the Levitical prohibition were meant to be a direct comparison—“Do not lie with a male as you would lie with a woman”—then kemo would be the obvious choice of words to set up that analogy. But it is not present, either in Leviticus 18:22 or 20:13.

The omission of kemo suggests that this prohibition may not be a direct analogy between male-male and male-female intercourse, but rather a prohibition of specific forms of ‘lyings’—perhaps those previously outlined in the Holiness Code. In other words, rather than saying, “Do not lie with a male in the same way that you lie with a woman,” these verses might mean: “Do not lie with a male the lyings of a woman [already prohibited in the preceding verses]. Just as there are certain women with whom you may not have sex due to kinship or ritual status, so too there are certain males with whom you may not have sex under those same conditions.” The legislation would thus extend to both genders the prohibitions previously applied only to one.8

The Meaning of To’evah

As we have seen, the central concern of the Holiness Code is to maintain Israel’s purity as a people set apart by God. Many of the regulations in this section of the Hebrew Bible address sexual behavior, dietary restrictions, and religious observance, linking violations of the law to ritual impurity or uncleanness.9

A key term in these prohibitions is to‘evah (תּוֹעֵבָה), commonly translated as “abomination.” While modern readers often assume that to’evah denotes moral depravity, its broader lexical range in biblical Hebrew suggests that it refers more generally to boundary violations: acts that transgress Israel’s divinely ordained social and ritual order, or indeed any action or thing that incites horror or disgust.10 While some instances of to’evah in the Hebrew Bible do carry moral weight, the term is also applied to a wide range of ritually or socially unacceptable practices, including:

Breaking dietary laws (Deut 14:3)

Dishonest business dealings (Deut 25:16)

Sacrificing the wrong animals (Deut 17:1)

Jacob Milgrom, a leading scholar on the Book of Leviticus, argues that in these and similar contexts, to‘evah does not signal moral evil per se, but rather a boundary violation—an action that defiles Israel’s covenantal holiness and disrupts the established religious order.11

This distinction is crucial when interpreting Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13. The usage of to’evah in these verses appears to align more closely with the ritual purity prohibitions mentioned above than with condemnations of moral evil. The structure of Leviticus 18-20 itself supports this reading. The section begins with a clear warning:

“You shall not do as they do in the land of Egypt, where you lived, and you shall not do as they do in the land of Canaan, to which I am bringing you. You shall not walk in their statutes.” (Lev 18:3)

Leviticus then presents a detailed list of prohibited sexual and religious practices, ranging from incest to bestiality and even child sacrifice to Moloch, before concluding with a warning that all these actions defile the land and will result in Israel’s expulsion:

“Be careful to observe all my statutes and all my decrees; otherwise the land where I am bringing you to dwell will vomit you out. Do not conform, therefore, to the customs of the nations whom I am driving out of your way, because all these things that they have done have filled me with disgust for them. But to you I have said: You shall take possession of their land. I am giving it to you to possess … To me, therefore, you shall be holy; for I, the Lord, am holy, and I have set you apart from other peoples to be my own.” (Lev 20:22-26)

This framing emphasizes Israel’s distinctiveness as a people set apart by the covenant. The Holiness Code is not primarily concerned with establishing universal moral laws, but with differentiating Israel from the surrounding nations and preventing contamination by their foreign customs. Israel is to remain “clean,” unlike the nations, which became “unclean” due to their sexual immorality and idol worship.

The Canaanite religious context is particularly important for understanding these prohibitions. Leviticus 18:3 explicitly warns against imitating Canaanite religious customs, which were highly sexualized and centered on fertility rituals designed to secure divine favor and ensure agricultural abundance.12

One of the most well-documented sexual practices in Canaanite religion was sacred prostitution, in which men and women engaged in ritual sex with temple functionaries as an act of devotion to the fertility gods. Deuteronomy 23:17–18 prohibits Israelite men and women alike from becoming “temple prostitutes” (qadesh and qedeshah, respectively), which suggests that men may have participated in these rituals as receptive partners in same-sex intercourse. Therefore, John Boswell proposes that Leviticus 18:22 may have originally been intended to prohibit Israelite participation in these cultic practices, rather than issuing a universal ban on all male-male sexual relations.13

Interestingly, within Leviticus 18–20, the word to’evah only appears in Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13. The Levitical authors do not label even the heinous crime of child sacrifice to Moloch (Lev 18:21; 20:1–5) as to’evah. If to’evah were primarily intended to denote grave moral evil, it is difficult to explain why it is not applied first and foremost to idolatrous child sacrifice. Are we to believe that the authors of Leviticus regarded male-male intercourse as a greater offense than the ritual killing of children? This seems unlikely.

Instead, its selective use in Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 suggests that the term does not primarily indicate moral depravity, but rather reinforces the boundaries of ritual purity. Perhaps, among the various transgressions of the law listed in these chapters, this violation was of particular concern to the Levitical authors—so much so that they felt the need to reiterate the boundary with an explicit declaration: “to’evah hi”—“it is an abomination.”

Comparison with Ancient Near Eastern Laws

Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 are the only laws in the Hebrew Bible that explicitly address male-male sexual relations. Unlike prohibitions against adultery or incest, for example, which appear in multiple Biblical legal collections, these verses have no direct parallels in other Israelite laws. The uniqueness of these two prohibitions has led scholars to explore their potential influences from surrounding cultures in the ancient Near East.

The legal codes and social customs of neighboring civilizations demonstrate that male-male sexual relations were not categorically prohibited, but regulated based on concerns about social hierarchy, family structure, and male honor. The Hittite Laws (ca. 1650–1500 BC), for example, prohibited a man from having sexual relations with his mother, daughter, or son. However, there is no general ban on male-male sex, suggesting that incest, rather than same-sex intimacy per se, was the primary concern.14

The Middle Assyrian laws (ca. 1076 BC) criminalized the forceful penetration of a freeborn man by another male of equal status, treating it as an act of humiliation akin to rape.15 However, the law is silent on consensual acts between freeborn men, or between a male of higher status and a male of lower status. This reflects a hierarchical, honor-based framework, in which a man’s dignity depended on his active, dominant role in sex.

Beyond the ancient near East, male-male relationships were often tolerated—but only under specific conditions. In classical Greece (ca. 5th–4th centuries BC), for example, male-male relationships were often structured within a pederastic framework, in which an older man (erastês) took on a mentoring role for a younger male (erômenos).16 This relationship was not purely sexual but also educational and social, reinforcing elite male networks. The younger male partner, however, was expected to transition into a dominant, active role in adulthood. A fully grown man who remained in a passive role was often ridiculed as unmasculine.17

Roman sexual ethics were even more rigid in their status-based prohibitions. A freeborn Roman citizen could engage in male-male relations, as long as he was the active partner. The receptive male partner was expected to be a slave, prostitute, or non-citizen, as passivity in sex was considered dishonorable for freeborn Roman men.18 In fact, Olyan notes that conquering armies would often humiliate their enemies by sexually subjugating them, making them “the equivalent of women.”19

In any case, none of these ancient societies, whether in the near East or the wider Greco-Roman world, categorically prohibited male-male intercourse. Rather, their laws place specific restrictions on it, including common-sense prohibitions of sexual violence and incest as well as laws designed to protect male social status.20 These prohibitions were not based on an abstract moral condemnation of same-sex intimacy, but on concerns tied to gender roles, family structures, and power dynamics.

Within this surrounding cultural framework, it seems likely that Levitical prohibitions had less to do with a moral condemnation of anything like “homosexuality” as it is understood today, and more to do with reinforcing Israel’s own gender and status hierarchies. The phrase mishkevei ishah (“the lyings of a woman”) itself suggests that the primary concern is the disruption of gender roles—specifically, the feminization of one male partner, which would have been perceived as a dishonor in a patriarchal society. It is likely this violation of gendered social order that was originally deemed to’evah, not because of an intrinsic moral defect, but because it constituted a ritual transgression that threatened Israel’s purity and rendered the land unclean.21

Redactional Expansion

Saul Olyan argues that Leviticus 20:13 may represent a later redactional expansion of Leviticus 18:22, reflecting a growing concern within the Holiness Code about Israel’s assimilation into surrounding cultures. While both verses prohibit male-male intercourse, there are notable differences in how they frame the prohibition. Leviticus 18:22 simply states that the act of lying with a male “the lyings of a woman” is to’evah, but does not specify a penalty. Leviticus 20:13, however, intensifies the prohibition by prescribing the death penalty for both participants, shifting from an implicit restriction to an explicit legal judgment. This development, Olyan suggests, may reflect an increasing anxiety on the part of the Levitical authors about Israel’s distinctiveness in the face of cultural influences from neighboring peoples.

Olyan suggests that the original purpose of Leviticus 18:22 was likely to prohibit specific male-male practices associated with pagan religious or social customs, such as temple prostitution or pederasty. However, as fears of assimilation intensified, a later redactor of the Holiness Code may have broadened the prohibition in Leviticus 20:13, transforming what was once a more limited or situational restriction into a categorical ban on all male-male sexual acts: “The land cannot tolerate uncleanness … Therefore, all who participate in any of the enumerated violations are a threat to the land’s purity and must be punished accordingly.”22

This redactional expansion bears striking similarities to a later development in Jewish legal thought known as “making a fence around the law” (s’yag la-Torah), a principle articulated in Pirkei Avot 1:1.23 In rabbinic tradition, this principle refers to expanding prohibitions beyond the explicit biblical command in order to prevent even the possibility of transgression. A well-known example is the Torah’s prohibition against boiling a young goat in its mother’s milk (Exod 23:19), which later rabbinic law expanded into a total ban on mixing meat and dairy. In a similar way, Leviticus 20:13 appears to be an attempt to “make a fence” around the earlier law in v. 18:22, ensuring that male-male intercourse was fully prohibited under any circumstances, rather than just within a specific cultural or ritual context.

If Olyan is correct, this would suggest that the biblical prohibition of male-male intercourse did not begin as a sweeping moral condemnation but as a targeted legal restriction that was later expanded. Rather than being a timeless expression of moral law, Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 reflect a process of legal development shaped by historical and cultural concerns—namely, the fear that Israel was backsliding into Canaanite and Egyptian practices. This historical-critical approach challenges the traditional assumption that these verses articulate an unchanging divine law and instead suggests that their meaning and application evolved over time.

Preliminary Conclusions

One thing is certain as we come to the end of this close reading of Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13. These verses are far more complex than they appear. The Hebrew phrasing is ambiguous in ways that open up numerous potential interpretations. The structure of the Holiness Code places these laws within the broader context of Israel’s ritual purity concerns, suggesting that these verses have more to do with transgressions of the law than moral condemnation. Comparative studies show that similar prohibitions in the ancient world were rooted in cultural notions of honor and hierarchy rather than a universal rejection of same-sex relations. Finally, Olyan’s redaction theory suggest that the Levitical authors may themselves have broadened the prohibition from a narrow rejection of pagan sexual practices to a more expansive condemnation in an attempt to “make a fence around the law.”

These insights call into question the traditional assumption that Leviticus presents an unequivocal moral condemnation of homosexuality. Instead, they suggest that these laws reflect specific historical, cultural, and ritual concerns, rooted in a particular social framework, which does not map neatly onto contemporary moral questions.

With this textual and historical foundation in place, we can now turn to the evolving interpretations of these passages in Jewish and Christian tradition, examining how they have been understood, applied, and reinterpreted over time.

Evolving Interpretations of Leviticus: From Philo to Aquinas

As we have seen, the meaning of Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 in their original context is not self-evident. It is unsurprising, then, that these prohibitions did not maintain a single, unchanging interpretation across Jewish and Christian traditions. From Second Temple Judaism to the medieval scholastics, these verses were shaped by shifting theological concerns, from ritual purity and cultural boundary-keeping to the emerging framework of Christian natural law. In this section, we will traces the history of these interpretations, exploring how changing cultural, philosophical, and theological lenses reshaped the meaning of these verses across the centuries.

Jewish Interpretations

A consistent theme in the earliest Jewish interpretations of Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 is the emphasis on Israel’s distinctiveness from surrounding nations. This boundary-focused interpretation became particularly important in the aftermath of Jewish encounters with Greek and Roman sexual norms. One of the earliest recorded extra-biblical critiques of male-male intercourse comes from Philo of Alexandra (ca. 20 BC-50 AD), who describes male-male intercourse as an “imitating of women’s ways.”24 This condemnation appears to be influenced by both the ritual purity concerns of Leviticus and Greco-Roman anxieties about masculinity and passivity, particularly the belief that engaging in the receptive role in male-male intercourse degraded one’s rational faculties.

With the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD, Jewish legal interpretation shifted toward the oral traditions later codified in the Mishnah (ca. 200 AD) and the Talmud (ca. 500 AD). These rabbinic texts expanded the application of Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 to new legal contexts. The Mishnah (Sanhedrin 7:4) lists male-male intercourse as a capital offense, reaffirming the penalty prescribed by Lev 20:13.25 However, later rabbinic debates over these laws reveal important areas of disagreement and nuance. Talmudic discussions in Sanhedrin 54a-55a address whether both partners in a male-male sexual act are equally culpable. Some argue that only the active partner is guilty, while others extend liability to both partners, depending on whether coercion, age, or status differences were involved.26 This suggests that the tension between Lev 18:22 and 20:13 continued to be a live question for rabbinic interpretation.

The Sifra, an early midrashic commentary on Leviticus (4th century AD), again reinforces the prohibition on male-male intercourse as a boundary marker of Jewish identity. It explicitly links the ban to foreign customs, emphasizing that sexual practices common in Egypt and Canaan must be rejected to maintain Israel’s holiness:

“You shall not do as they do in the land of Egypt, nor as they do in the land of Canaan. What did they do? A man would marry a man, and a woman would marry a woman. Therefore, Scripture says, ‘You shall not do as they do’—to teach that these are their abominable practices, and you shall not imitate them.”27

The Tanchuma, a later midrash (5th-7th century AD), reflects a growing tension in rabbinic thought. In some passages, it frames male-male intercourse as a severe transgression, while distinguishing it in others from inherently evil acts like adultery, idolatry, and murder.28 This is a significant distinction, as it indicates that rabbinic authorities did not place male-male intercourse at the highest tier of moral offenses. Unlike medieval Christian theologians, who were at this time beginning to universalize the Old Testament prohibitions on male-male relations as part of the emerging framework of natural law, Jewish interpreters continued to regard it as part of the ritual purity laws.

Finally, the Tosefta, an early rabbinic legal supplement to the Mishnah, introduces a more nuanced approach to applying Leviticus 20:13 and Sanhedrin 7:4. While recognizing that male-male intercourse was forbidden by the law, it allows that not all cases warranted capital punishment.29 This further implies that the Levitical prohibition on male-male relations was not regarded as absolutely immoral by later rabbinic authorities. Circumstances mattered, and judicial restraint was warranted.

Early and Medieval Christian Interpretations

Early patristic writings frequently cite the Levitical prohibitions in conjunction with the story of Sodom. The Constitutions of the Holy Apostles (ca. 375-380 AD) cites both Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 in its condemnation of “the sin of Sodom” as “contrary to nature … for thus say the oracles: ‘Thou shalt not lie with mankind as with womankind.’ ‘For such a one is accursed, and ye shall stone them with stones: they have wrought abomination.’”30

Interestingly, in a later passage, the Constitutions again cites Leviticus 18:22, but this time with an explicitly pederastic interpretation: “‘Thou shall not corrupt boys:’ for this wickedness is contrary to nature, and arose from Sodom, which was therefore entirely consumed with fire sent from God.”31 This suggests that the authors of the Constitutions were aware of the ambiguity in Leviticus 18:22 introduced by the use of the word zakar.

St. Basil the Great (ca. 329-379 AD) references Leviticus 20:13 in his disciplinary canons for the Eastern churches, ordaining that “the man who is guilty of unseemliness with males will be under discipline for the same time as adulterers. This is the same as the law lays down against both. ‘If a man lie with a male as with a female, both of them have committed an abomination; they shall surely be put to death.’”32 Here, Basil does not frame male-male intercourse as an especially heinous “crime against nature,” but rather as a sexual transgression akin to heterosexual fornication.

By the early Middle Ages, however, Christian interpreters began to depart from the Jewish interpretative tradition. As we have seen, while the rabbinic authorities continued to treat these texts as part of the ritual purity code, Christian thinkers increasingly read them as universal moral prohibition. This was perhaps an inevitable shift, since Christians did not consider the laws of the Holiness Code binding under the New Covenant (cf. Acts 10:9–16). If Christians wanted to retain the prohibition on male-male relations, then, they would have to reinterpret these prohibitions as grounded in universal reason and natural law.

St. Thomas Aquinas and the Western scholastic tradition thoroughly codified the notion that Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 prohibited male-male relations, not as a matter of ritual purity, but as violations of the divinely ordained sexual order. The developing theory of natural law posited that sexual relations should be directed toward procreation, and any deviation from this purpose was considered unnatural. Aquinas categorized sins against nature, such as sodomy and bestiality, as grave offenses:

“Wherefore among sins against nature, the lowest place belongs to the sin of uncleanness, which consists in the mere omission of copulation with another. While the most grievous is the sin of bestiality, because use of the due species is not observed … After this comes the sin of sodomy, because use of the right sex is not observed.”33

By the end of the twelfth century, these prohibitions were integrated into canon law. The Third Lateran Council in 1179 decreed that individuals guilty of such unnatural vices should face severe ecclesiastical penalties:

“Let all who are found guilty of that unnatural vice for which the wrath of God came down upon the sons of disobedience and destroyed the five cities with fire, if they are clerics be expelled from the clergy or confined in monasteries to do penance; if they are laymen they are to incur excommunication and be completely separated from the society of the faithful.34

This universal condemnation of male-male sexual acts remained virtually unchallenged throughout the Christian world from the Middle Ages until the early modern period.

Modern Scholarship and Reconsiderations

With the rise of historical-critical scholarship in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Biblical scholars began to distinguish more rigorously between ritual impurity laws and universal moral prohibitions in Old Testament legal texts. This distinction posed a direct challenge to the Christian reception of Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13, which had been assumed—at least since the Middle Ages—to articulate an absolute and timeless moral norm. As we have seen, scholars like Jacob Milgrom and John J. Collins have argued that these laws originally functioned within an ancient Near Eastern legal and ritual framework, rather than as unchanging moral prescriptions binding on all people for all time.35 If these verses were primarily concerned with preserving Israel’s covenantal distinctiveness, rather than defining an unchanging moral order, then their application in Christian ethics is far from self-evident.

Thus, we arrive at a crucial question: Does Catholic moral theology still rely on Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13, even if only implicitly? If so, on what basis does it maintain these verses as expressions of divine law while disregarding other prohibitions of the Holiness Code as mere historically- and culturally-bound practices? And if these verses have quietly faded from current Magisterial discourse, does this suggest an unspoken recognition of their unreliability?

The Church’s Reception and Application of the Levitical Texts

The Catechism of the Catholic Church defines homosexual acts as “intrinsically disordered” and appeals to a range of Scriptural texts as evidence, citing Genesis 19:1-29, Romans 1:24-27, 1 Corinthians 6:10, and 1 Timothy 1:10. However, it omits any mention of the Levitical prohibitions, instead stating:

“Basing itself on Sacred Scripture, which presents homosexual acts as acts of grave depravity (cf. Gen 19:1-29; Rom 1:24-27; 1 Cor 6:10; 1 Tim 1:10), tradition has always declared that ‘homosexual acts are intrinsically disordered’ (Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Persona Humana, 8). They are contrary to the natural law. They close the sexual act to the gift of life. They do not proceed from a genuine affective and sexual complementarity. Under no circumstances can they be approved” (CCC 2357).36

The fact that the Catechism skips over any reference to Leviticus here suggests a deliberate interpretive choice. If Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 were as central to the Church’s case against same-sex acts as they have long been assumed to be, one would expect them to appear alongside the story of Sodom and Gomorrah and the Pauline texts. Their absence implies that the Church at least implicitly acknowledges that these passages pose particular exegetical challenges.

By contrast, Leviticus is mentioned in the 1986 CDF document Homosexualitatis problema, albeit briefly. In this document, the Congregation inveighs against “a new exegesis of Sacred Scripture which claims variously that Scripture has nothing to say on the subject of homosexuality, or that it somehow tacitly approves of it, or that all of its moral injunctions are so culture-bound that they are no longer applicable to contemporary life.”37 It condemns these new exegetical approaches as “gravely erroneous” and claims “a clear consistency within the Scriptures themselves on the moral issue of homosexual behaviour.”38 It then engages in a brief overview of the Scriptural sources:

“In Genesis 3, we find that this truth about persons being an image of God has been obscured by original sin. There inevitably follows a loss of awareness of the covenantal character of the union these persons had with God and with each other. The human body retains its ‘spousal significance’ but this is now clouded by sin. Thus, in Genesis 19:1-11, the deterioration due to sin continues in the story of the men of Sodom. There can be no doubt of the moral judgment made there against homosexual relations. In Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13, in the course of describing the conditions necessary for belonging to the Chosen People, the author excludes from the People of God those who behave in a homosexual fashion.”39

This reference is theologically revealing. Even here, where the CDF is attempting to show the clear consistency of the Scriptures in condemning same-sex acts, it acknowledges that the Levitical prohibitions are found in the context of the Holiness Code—laws governing membership in the Chosen People. It does not assert that these verses were intended to establish a universal moral prohibition.

This brief, measured reference to Leviticus is the only one I have been able to find anywhere in the Church’s recent documents on homosexuality. The absence of any further engagement with Leviticus in this document, or indeed anywhere in the modern Magisterium, almost suggests an air of embarrassment, as though these prohibitions are best left behind in contemporary articulations of moral theology.

However, even as the Magisterium has distanced itself from citing Leviticus, Catholic tradition continues to assume the moral weight of these prohibitions. As we have seen, Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 played a significant role in the historical development of Catholic teaching on homosexuality. If the Church now recognizes that these verses may be more nuanced and complex than once assumed, then openly recognizing these complexities could be the beginning of a broader conversation about how the Church interprets Scripture in light of historical, linguistic, and cultural insights. Just as the Church no longer upholds Levitical laws on dietary restrictions or mixed fabrics as binding, we must critically reassess whether the prohibitions of Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 remain relevant to moral theology today.

Conclusion: Reassessing the Role of Leviticus in Moral Theology Today

Our examination of Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 has revealed that their meaning is far less straightforward than commonly assumed. While these verses have often been wielded as absolute moral prohibitions against same-sex relations, our study suggests that they may not be universal moral precepts at all, but rather specific regulations within the Holiness Code, designed to distinguish Israel from its surrounding nations.

Key Findings

First, the specificity of the prohibitions in Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 must be considered. The lack of clarity in the Hebrew phrasing, the association of these laws with ritual purity concerns, and their situational parallels to other ancient Near Eastern legal codes suggest that these verses may have been directed not against all same-sex relationships, but rather against certain ritualized or socially destabilizing practices, such as Canaanite temple prostitution, incestuous relationships, or pederasty.

Second, the concern with gender roles appears to play a significant role in these prohibitions. The phrase mishkevei ishah (“the lyings of a woman”) suggests that the issue at stake may not be sexuality per se, but rather the feminization of the male partner in a patriarchal society where such a role reversal was considered dishonorable. This reading aligns with broader ancient Mediterranean concerns about honor, shame, and the preservation of social hierarchy. If these laws were written to reinforce gender norms rather than articulate an absolute moral principle about same-sex intimacy, then their applicability in contemporary moral theology is far from clear.

Third, the distinction between ritual purity and moral goodness is crucial. Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 belong to the Holiness Code, which establishes Israel’s distinctiveness through ritual purity laws, including dietary restrictions, fabric prohibitions, and other ceremonial commands that are no longer observed by Christians. While some moral principles do emerge from the Holiness Code, scholars such as Jacob Milgrom and John J. Collins have demonstrated that these texts primarily functioned as identity markers rather than expressions of universal, natural law. If this distinction is granted, then it is doubtful whether these verses have any role to play in contemporary Catholic moral teaching on homosexuality.

Implications for Theological Inquiry

As this study has demonstrated, the meaning of Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 is far from clear-cut. While these verses have historically been invoked as absolute prohibitions against same-sex relationships, a closer examination of their linguistic, cultural, and ritual context reveals a far more complex and historically contingent meaning. Notably, the Church’s own interpretation of these texts has evolved over time. In the last fifty years, direct references to Leviticus have all but disappeared—a tacit acknowledgment, perhaps, of the exegetical difficulties that these texts present.

However, if Church teaching on homosexuality has, even in part, been shaped by a misreading or misapplication of Leviticus, this raises urgent and far-reaching questions about the broader framework of Catholic sexual ethics. It is not enough to sidestep these issues by selectively omitting Leviticus from contemporary discussions while still implicitly relying on its historical influence in the development of Catholic doctrine on homosexuality. A more rigorous exegetical method is required, one that can withstand critical scrutiny while remaining faithful to the pursuit of truth.

This study highlights the need for a true ressourcement in Catholic moral theology: a return to Scripture, informed not by inherited assumptions but by historically grounded, exegetically sound interpretation. If the Church’s moral teaching is to rest on a solid foundation, then that foundation must be continually tested, refined, and deepened through honest engagement with both Scripture and tradition, informed by the best available scholarship.

A responsible, intellectually honest approach to sexual ethics does not simply affirm past conclusions uncritically. Rather, it requires a careful examination of all the available data, a willingness to reexamine our inherited assumptions, and an openness to wrestling with the full complexity of the meaning, context, and application of the text, even when that investigation leads to tension and ambiguity.

Such an approach is not merely an academic exercise; it is a theological responsibility. If we truly believe that Scripture is the inspired Word of God, then we must read it as it actually is, not just as we have been conditioned to believe it must be.

This study does not claim to offer a final answer on the meaning of these texts, but it has at least demonstrated that Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 are not the clear, universal moral prohibitions they are often assumed to be. I hope it invites us all into a deeper, more honest engagement with the Scriptural foundations of Catholic moral theology.

The challenge before us now is urgent. Will the Church continue to rely on interpretations shaped more by tradition than rigorous exegesis? Or will we have the courage to engage these texts again with intellectual integrity and discernment, trusting that the Spirit of Truth will lead us into all truth (Jn 16:13)? For faithfulness to the living Word of God demands nothing less. To do otherwise is not to preserve tradition, but to diminish and betray it.

Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, “Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on the Pastoral Care of Homosexual Persons” (Homosexualitatis Problema), October 1, 1986, §5.

For example, “as with a woman” (NABRE, ESV, NLT); “as with womankind” (KJV); “as one does with a woman” (NIV); “as one sleeps with a female” (NASB), etc. For a representative sampling of all English translations of Leviticus 18:22, see Bible Gateway.

Saul M. Olyan, “‘And with a Male You Shall Not Lie the Lying Down of a Woman’: On the Meaning and Significance of Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 5, no. 2 (October 1994): 179–206.

James Swanson, Dictionary of Biblical Languages with Semantic Domains: Hebrew (Old Testament) (Oak Harbor: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 1997).

James Alison, “‘Sodomy’ and ‘Homosexuality’ Are Not Biblical Sins,” TheBody.com, November 28, 2023.

John Boswell, Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 100–102.

Swanson, Dictionary.

Alison, “Biblical Sins.”

Larry Toothman, “The Big Eight,” Global Alliance for LGBT Education (GALE), June 10, 1994.

The Lexham Analytical Lexicon of the Hebrew Bible (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2017).

Jacob Milgrom, Leviticus 17–22: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, vol. 3 of The Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 1488–1492.

John Day, Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000), pp. 83-86.

John Boswell, Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 101.

Olyan, “And with a Male,” 189-190.

Harry A. Hoffner, Jr., “Incest, Sodomy, and Bestiality in the Ancient Near East,” in Orient and Occident: Essays Presented to Cyrus H. Gordon on the Occasion of His Sixty-Fifth Birthday, ed. Harry A. Hoffner, Jr., Alter Orient und Altes Testament, vol. 22 (Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, 1973), 83.

Kenneth J. Dover, Greek Homosexuality (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978), 16–20.

Ibid, 85–87.

Olyan, “And with a Male,” 193.

Ibid, 192.

Ibid, 194-195.

See Olyan, “And With a Male,” 206. “Perhaps the insertive partner was originally condemned as a boundary violator because his act ‘feminized’ his partner or because he did not conform to his class (male) when he chose another male as a partner in intercourse.”

Toothman, “The Big Eight.”

The Mishnah, Pirkei Avot 1:1, trans. Herbert Danby (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1933).

Philo of Alexandria, Special Laws 3.39–42, in The Works of Philo, trans. F. H. Colson and G. H. Whitaker (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1937), pp. 569–571.

The Mishnah, Sanhedrin 7:4.

Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 54a–55a, in The Talmud of Babylonia: An American Translation, trans. Jacob Neusner (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1996), vol. 19, pp. 372–375.

Sifra on Leviticus 18:22, in Sifra: An Analytical Translation, trans. Jacob Neusner (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988), vol. 2, pp. 90–92.

Midrash Tanchuma, Acharei Mot 6, in Midrash Tanhuma-Yelammedenu: An English Translation of Genesis and Exodus, trans. Samuel Berman (Hoboken, NJ: Ktav Publishing House, 1996), pp. 230–232.

Tosefta Sanhedrin 14:4, in The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew with a New Introduction, trans. Jacob Neusner (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002), p. 575.

Constitutions of the Holy Apostles, 6.5.28, “Of the Love of Boys, Adultery, and Fornication,” in The Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 7, eds. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1886), 462.

Ibid, 7.1.2, “Moral Exhortations of the Lord’s Constitutions Agreeing with the Ancient Prohibitions Of The Divine Laws,” in The Anti-Nicene Fathers, vol. 7, 465.

St. Basil the Great, Letters, 217, in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 2nd series, vol. 8, eds. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1895), 223.

St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II-II, q. 154, a. 12, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province, accessed at newadvent.org.

Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils, vol. 1, ed. Norman P. Tanner (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1990), 217.

See Milgrom, Leviticus 17–22, and John J. Collins, Introduction to the Hebrew Bible, 3rd ed. (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2018).

Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1997).

Homosexualitatis problema, §4.

Ibid, §4-5.

Ibid, §6.