Can Catholics Ask Hard Questions About Theology?

The Tension Between Faith and Doubt

Introduction

For years, I skirted the tension between faith and doubt by simply accepting Church teaching as a monolith—complete, unassailable, unquestionable. I took it for granted that it must all be true, and that being a faithful Catholic required this a priori assumption. Those theologians I vaguely knew of on the margins of the Church—those who dared to question settled teachings, especially on hot-button issues of moral theology and social justice—struck me as irresponsible, unfaithful, even subversive. They weren’t engaging in legitimate theology, I thought. They were undermining the Church from within.

Then, one day, a monstrous crack appeared in the foundation of my certainty. A question emerged that I could not ignore—one that upended everything I thought I knew. And I realized, with dread, that trying to suppress it would mean clinging to certainty at the expense of truth, a choice that could only lead to the collapse of faith. If Catholicism was about truth, then I had no choice but to start asking the questions I had spent my life avoiding.

The English theologian James Alison has described theology as “a matter of survival.”1 As I navigate this tremendously unexpected and disorienting season of deconstruction, I have to agree. For me, theology has become a kind of cave diving—plunging into the abyss that has opened beneath the structure of my life, daring to see how deep it goes, and what, if anything, lies at the bottom.

The Role of Questioning in Catholic Tradition

Many Catholics assume, as I once did, that questioning Church teaching is a sign of weak faith, bad intentions, or even disobedience. Theological inquiry is fine, according to this model, as long as it stays within the boundaries of what has already been defined. There, like a lion in its cage or a neutered bull in the field, theology remains tame, predictable, safe.

The Church’s intellectual tradition tells quite a different story. Our greatest saints and theologians—men like Augustine, Aquinas, and Newman—were not passive recipients of doctrine, content to “stay in their lane” and endlessly regurgitate what they had received. They were bold questioners, relentless seekers of deeper understanding. They engaged the sciences and philosophies of their day, challenged settled assumptions, wrestled with complex questions, and pushed theological thought into uncharted waters. Each, in his own way, forged a new synthesis that shaped the mens ecclesiæ in ways previously unimagined.

Augustine: Wrestling with Faith and Reason

St. Augustine (354-403), one of the Church’s most celebrated theologians, spent years struggling to reconcile faith and reason. His own spiritual journey was marked by profound doubt and philosophical searching. It was only after immersing himself in the intellectual traditions of Neoplatonism and wrestling with the problem of evil that he came to embrace Christianity in a way that fully engaged both heart and mind. His famous prayer—“Lord, let me know myself, let me know You”—captures this dynamic.2 For Augustine, the pursuit of God and the pursuit of truth were inseparable.

Aquinas: The Model of Rigorous Inquiry

St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) followed a similar path. Unlike some of his contemporaries, who viewed philosophy as a threat to faith, St. Thomas saw it as a tool for deeper understanding. Aquinas “baptized” Aristotle and the best available scientific knowledge of his time, integrating faith and reason in a synthesis that continues to shape Catholic thought today. He did not simply accept theological assertions; he rigorously interrogated them, using the Scholastic method which he elevated to an art form. His Summa Theologiae is structured as a series of objections and responses, modeling an intellectual tradition in which the hardest and most challenging questions are engaged head-on.

Newman: Doctrine as a Living Tradition

St. John Henry Newman (1801-1890), one of the most significant theological figures of the modern era, argued that questioning is not only permissible in theology but essential to its growth. In his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, he demonstrated that doctrine is not static and immutable, but unfolds over time, developing gradually as the Church encounters new historical, cultural, and intellectual contexts. “Here below,” he wrote, “to live is to change, and to be perfect is to have changed often.”3 Without theological inquiry, doctrine would stagnate. It is only through engagement with new questions that the Church’s teachings become more fully articulated.

John Paul II: Faith and Reason in Harmony

St. John Paul II echoed this sentiment in his encyclical Fides et ratio (1998): “Faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth.”4 If one wing is missing, we cannot ascend. Theology without reason becomes fundamentalism; reason without faith cannot reach the highest truths. The Catholic intellectual tradition thrives precisely because it embraces both.

The Difference Between Doubt, Dissent, and Responsible Inquiry

Not all questioning is equal, however. Theology is a discipline that requires careful distinctions, and nowhere is this more important than the difference between doubt, dissent, and responsible inquiry. These terms are often conflated, but they are not interchangeable.

Doubt

Even the greatest saints have wrestled with doubt. The experience can be constructive or destructive of faith, depending in large part on whether we engage our doubts in a spirit of trust or allow them to fester into cynicism and despair.

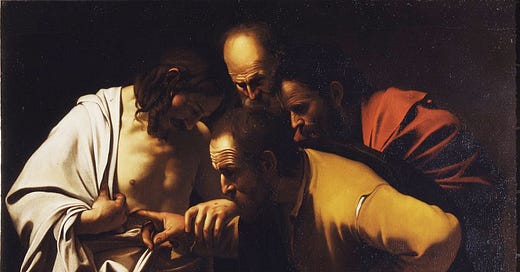

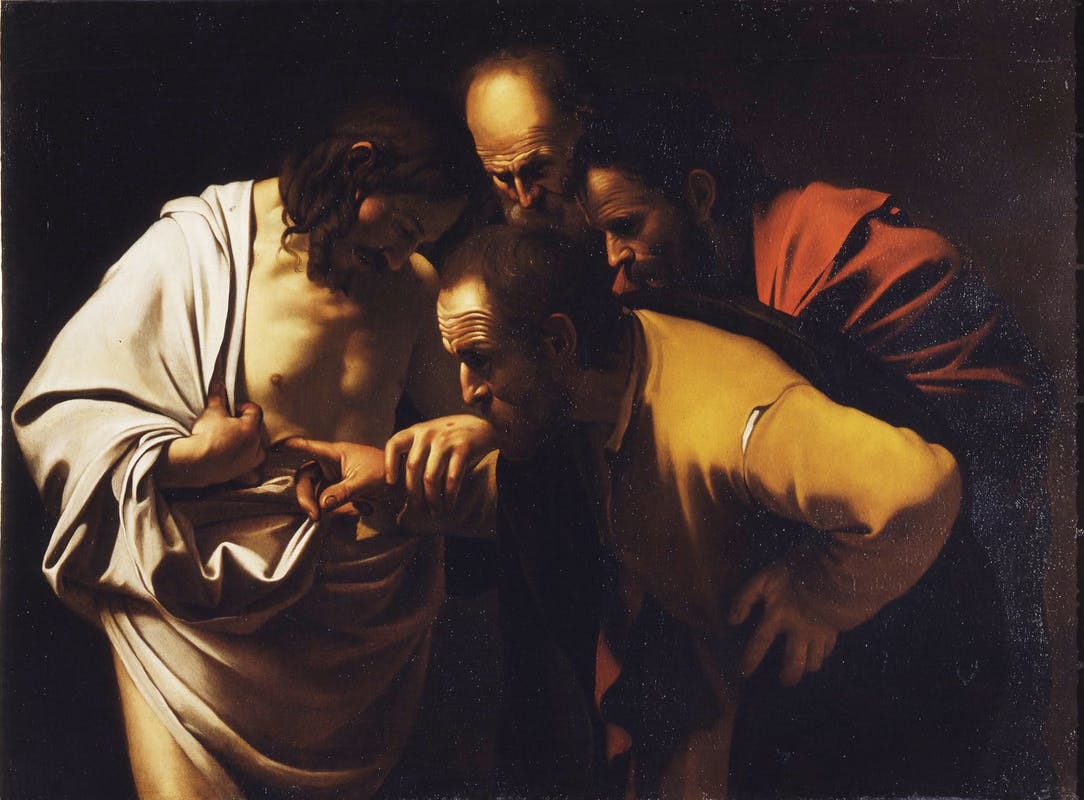

Consider St. Thomas the Apostle, often remembered (unfairly) as “Doubting Thomas.” When he refused to believe in the Resurrection without firsthand proof, he was not rejecting faith in Jesus, but expressing the very human need for certainty. His doubt, however, did not lead him away from Christ—it led him to Christ. When Jesus appeared to him and invited him to touch His wounds, Thomas responded with one of the most profound confessions of faith in Scripture: “My Lord and my God!” (John 20:28).

Thomas’s story reveals that doubt, when engaged honestly, can be a catalyst for deeper belief. However, when doubt turns into radical skepticism—where no truth is ever accepted, and every belief is perpetually suspended—it ceases to be a step toward faith and instead becomes a barrier to it.

Dissent

The Church does not forbid asking difficult questions. Catholics may struggle with teachings of the Church, seek clarification, and engage in theological reflection. However, the Dogmatic Consitution on the Church, Lumen Gentium, does emphasize that Catholics are called to give religious assent to the Church’s official teachings, even when we may not fully understand or agree with them.5 Questioning becomes dissent when a Catholic publicly rejects a definitive doctrine of the Church, rather than engaging with it in a spirit of faith seeking understanding.

At the same time, not all teachings carry the same weight or demand the same level of assent. The Church distinguishes between three levels of doctrinal authority:

Dogmas (credenda): Divinely revealed truths that the Church has formally defined (e.g., the Trinity, the divinity of Christ). These require the full assent of faith. To obstinately deny a dogma of the Church constitutes heresy, placing one outside the Catholic faith.

Definitive doctrines (tenenda): Teachings that, while not divinely revealed, are historically or logically derived from revelation and proposed as definitively to be held (e.g., the immorality of abortion, the invalidity of women’s ordination). These teachings require firm and definitive assent, though they do not rise to the level of dogma. To deny a definitive doctrine constitutes dissent.

Non-definitive doctrines: Teachings that are neither divinely revealed nor infallibly defined but are presented by the Church as true, or at least as sure. These require religious submission of will and intellect, meaning the teaching should be respected and adhered to, but legitimate theological development is possible.6

Understanding these distinctions is essential, because not all questioning constitutes dissent. A Catholic who critically examines a non-definitive doctrine in light of Scripture, Tradition, and reason is not in the same position as one who denies a dogma of the faith or definitive doctrine of the Church. The 1990 instruction Donum Veritatis explicitly recognizes that many doctrines have not yet been definitively settled, and that theologians, when acting in good faith, “must have the freedom to pursue research in the service of truth, [provided that] this freedom is exercised within the Church’s faith.”7

This means that while theologians are not free to reject dogmatic teachings or definitive doctrines of the Church, they do have a responsibility to clarify, deepen, and refine the Church’s understanding of doctrine over time—especially in areas where that doctrine has not yet been adequately articulated or where new questions emerge from historical, scientific, or philosophical developments.

Responsible Inquiry

Unlike dissent, which assumes a posture of rejection, responsible theological inquiry remains within the bounds of faith, as Donum Veritatis requires, seeking understanding rather than undermining belief. The Church has long recognized that some doctrines require deeper articulation, and theologians play a crucial role in engaging difficult questions with both intellectual rigor and fidelity to the tradition.

Let us consider again the example of St. Thomas Aquinas, whose work was once viewed with deep suspicion because of his engagement with Aristotelian philosophy. Many in his time feared that bringing pagan philosophical categories into theology would corrupt the purity of Christian teaching.

Aquinas, however, believed that truth is one. Wherever it is found, whether by faith or reason, it ultimately comes from God, who is truth itself. In his Summa Theologiae, he not only synthesized theology with philosophy in a remarkable way; he also systematically engaged objections to Church teaching, demonstrating that serious questioning is not a danger to faith but a necessary part of refining and deepening it.

The Church ultimately recognized the value of Aquinas’s work. Today, he is a Doctor of the Church and regarded as one of the greatest Latin theologians in history. Yet, during his own lifetime, his writings were controversial—even condemned in some places—before being fully received by the Magisterium. This illustrates an important reality: some of the theological work we take for granted today as foundational was once considered “borderline.”

The Church as Both Guardian and Developer of Doctrine

The Catholic Church understands itself to be the guardian of divine revelation, entrusted with preserving the faith handed down from the apostles. Yet, history shows that this guardianship does not mean doctrine is static or unchanging. Rather, the Church’s understanding of doctrine has developed over time, deepening in response to new historical, cultural, and intellectual contexts.

The Magisterium, the Church’s teaching authority, has the dual responsibility of both safeguarding doctrine and allowing it to develop organically. This means that while core truths of the faith remain unchanged, the Church’s understanding, articulation, and application of these truths can and must evolve.

The 5th-century theologian St. Vincent of Lérins articulated this principle in his famous analogy of doctrinal development:

“Let understanding, knowledge, and wisdom increase and make great and vigorous progress, both in individuals and in the whole Church, in each generation and in the course of ages—but only within its proper limits, that is, within the same doctrine, the same meaning, and the same judgment.”8

His words anticipate the later reflections of St. John Henry Newman, who would argue that doctrinal development is not a rupture with the past, but the natural outgrowth of what was already present, akin to the development of a living organism.

Historical Examples of Doctrinal Development

History provides numerous examples of how the Church’s understanding of moral and social issues has developed over time.

1. Religious Freedom

For centuries, the Church held that Catholicism should be privileged by the state, and that religious error should not be tolerated. The famous maxim “error has no rights” was used to justify the suppression of non-Catholic religious practice.

However, at Vatican II, the Church made a dramatic shift. Dignitatis Humanae (1965) affirmed religious liberty as a fundamental human right, arguing that it belongs to the dignity of the human person to seek the truth and adhere to it once it is found:

“This Vatican Council declares that the human person has a right to religious freedom. This freedom means that all men are to be immune from coercion on the part of individuals or of social groups and of any human power, in such wise that no one is to be forced to act in a manner contrary to his own beliefs.”9

This was not a contradiction of prior teaching, but a development of doctrine—one that recognized the dignity of human conscience in a new way.

2. Slavery

The early Church did not explicitly condemn slavery, and for centuries, it was tolerated as a social institution. Even well into the medieval period, many theologians accepted it as a given. However, as Christian reflection on human dignity deepened, so did the Church’s moral stance on slavery.

By the nineteenth century, the Church had fully condemned the institution. Pope Gregory XVI, in his 1839 encyclical In Supremo Apostolatus, issued one of the strongest papal condemnations of the practice:

“We prohibit and strictly forbid any ecclesiastic or lay person from presuming to defend as permissible this trade in humans under any pretext or excuse.”10

Again, this was not a reversal of prior teaching, but an authentic development. What the Church had once tolerated as a necessary evil was explicitly condemned when it became clear, in the course of time, that the Church’s own understanding of human dignity could no longer permit it.

3. Usury

For centuries, the Church condemned all lending at interest as intrinsically immoral, based on biblical prohibitions (cf. Ex 22:25; Lk 6:34-35). The medieval Church held that charging interest—even at a modest rate—was a form of exploitation and unjust gain.11

However, as economic structures evolved and the understanding of finance became more sophisticated, theologians began to distinguish between exploitative lending and legitimate investment. By the early modern period, theologians Michael Lawler and Todd Salzman report,

“The profiting from loans at interest continued and grew, until in the 1830s, in response to further questions, a new Roman formula emerged: non est inquietandum, a penitent taking interest ‘was not to be disturbed’. What had been a solemn teaching condemning usury was allowed to fade into oblivion, and what was originally gravely sinful, namely, taking interest on loans, became accepted moral practice.”12

Today, lending at interest is not considered intrinsically immoral, though usurious, exploitative lending remains condemned (CCC §2269).13

Newman’s Theory of Doctrinal Development

Cardinal John Henry Newman, in his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, outlined how doctrine grows over time without being either invented or distorted. He argued that the Church does not create new truths, but rather unfolds what has been implicit in revelation from the beginning: “A development, to be faithful, must retain its essential idea and principles; it must be a true continuation of the past, not a contradiction.”14

Newman proposed Seven Notes of Doctrinal Development, which serve as criteria for distinguishing authentic developments from distortions. Among them:

Continuity of Principle – True development preserves the essence of the original teaching.

Logical Sequence – Doctrinal growth follows from what has come before, rather than appearing arbitrarily.

Preservative Additions – Later developments clarify earlier truths rather than replace them.

A future post shall explore all seven of these notes in greater detail. Newman’s insights remind us, however, that authentic development does not mean rupture, but maturation. Doctrines develop in continuity with the deposit of faith while responding to new historical and intellectual contexts. The question before us today is how the Church’s doctrines, particularly in the realm of moral theology and human dignity, might continue to unfold in light of contemporary questions.

The Key Question: Can Doctrine Develop in Other Areas?

If doctrine has developed on issues like religious freedom, slavery, and economics, could it also develop in other areas—including moral theology and sexuality?

Many contemporary theologians argue that the Church must continue refining its understanding of human dignity, relationships, and embodiment in light of new insights from philosophy, psychology, and the natural sciences.

The Church has always insisted that authentic development does not contradict prior teaching but rather clarifies, deepens, and expands it. The challenge, then, is to discern where such development might be needed today, and the paths toward deeper understanding.

Conclusion: The Courage to Seek the Truth

To ask hard questions about theology is not a betrayal of faith. Rather, it is an act of faith in the God who is Truth itself. The history of Catholic thought bears witness to this. The Church’s greatest theologians were not those who blindly accepted inherited formulations, but those who sought deeper understanding, wrestling with complexity rather than retreating into the illusion of certainty.

Questioning is not the enemy of faith. It is the means by which faith matures.

Jesus Himself provides the model for us. He never condemned those who asked questions—only those who refused to see. When the scribes and Pharisees sought to trap Him in theological puzzles, He often responded with a question of His own, exposing the limits of their rigid certainties (cf. Mk 11:30; Mt 22:15-22, 41-46). And when Thomas, the doubter, demanded evidence, Jesus did not rebuke him, but met him where he was, inviting him to touch His wounds and believe (Jn 20:27-28).

The real danger for Catholics, then, is not theological inquiry, but the fear of it—the temptation to cling to familiar answers rather than risk encountering a deeper, fuller truth. But if God is Truth, then we have nothing to fear. The questions we ask in faith can only bring us closer to Him.

Catholics not only can ask hard questions about theology. We must.

Reflection Questions

What theological questions have you been afraid to ask?

What tensions between faith and doubt have you tried to ignore?

What might happen if we trust that seeking truth, no matter where it leads, can only bring us closer to God?

Alison, James, “Theology as Survival.” Interview by Brett Salkeld. Commonweal, March 6, 2012. https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/interview-james-alison.

Augustine, Confessions, X.1, trans. Henry Chadwick (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991).

John Henry Newman, An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (London: Longmans, Green, 1878).

John Paul II, Fides et ratio (Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1998), §1.

Second Vatican Council, Lumen Gentium (1964), §25.

Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, “Doctrinal Commentary on the Concluding Formula of the Professio fidei” (June 29, 1998).

Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Donum Veritatis (1990), §12.

St. Vincent of Lérins, Commonitorium, 23, trans. Thomas G. Guarino (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2013).

Second Vatican Council, Dignitatis Humanae (1965), §2.

Gregory XVI, In Supremo Apostolatus (1839).

Cf. Gratian, Decretum Gratiani, in J.P. Migne (ed.), Patrologiae Cursus Completus: Series Latina, vol. 187 (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, first published 1844-1855), 1406.

Lawler, Michael G., and Todd A. Salzman, “Usury and Homosexual Behaviour: Parallel Theological Tracks?” Modern Believing 54, no. 4 (2013): 194-195.

Catechism of the Catholic Church. 2nd ed. Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1997.

Newman, Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine.