For me, encountering the idea that homosexuality is a normal variation in human sexuality was a game-changer. It felt like my eyes had been opened to something fundamental—something that had been there all along, but that I had never allowed myself to see.

To people outside the Church, that might sound strange. How could someone not recognize something so obvious? But within the framework in which I had been formed as a Catholic, heterosexuality wasn’t just the statistical majority. It was the universal human norm. Within the framework of traditional Catholic anthropology, homosexuality (or to use the preferred term in Catholic circles, “same-sex attraction”) can only be seen as a deviation from that norm: an anomaly, a disorder, a sign that something has gone wrong in a person’s psychological or moral development.

For my entire adult life, I accepted this assumption. I believed that everyone is naturally heterosexual and that my own same-sex attraction was a deficiency, a wound, probably caused by childhood trauma or some disordered family dynamics. And if that were true, then the Church’s moral reasoning was logically consistent: same-sex relationships could never be morally good. The only “proper” path for someone like me was either lifelong celibacy or, depending on which Catholic therapists you listened to, some form of don’t-call-it-conversion-therapy to “heal” my disordered sexuality.

But what if the Church’s moral teaching on same-sex relationships is based on a false premise? What if heterosexuality is not the universal default setting for all human beings, but simply the majority condition? If the Church has misidentified the nature of human sexuality, then its entire moral framework regarding homosexuality—rooted in the assumption of universal heterosexuality—becomes untenable.

The Church’s Unspoken Assumptions About Homosexuality

For all its moral pronouncements on homosexuality, the Catholic Church has never taken an official, doctrinal position on what causes it. The Catechism acknowledges this uncertainty in a single sentence, stating that its “psychological genesis remains largely unexplained.”1

However, Catholic moral teaching implicitly assumes that same-sex attraction must be caused by an external factor—some disruption in the natural order—and that this factor is psychological. The logic underlying this position can be expressed as follows:

Heterosexuality is the universal and natural human norm. Any deviations from this norm must be caused by external factors.

Homosexuality is a deviation from heterosexuality.

Therefore, homosexuality must be caused by an external factor (e.g., trauma, developmental failure, etc.).

This perspective is implicit in various Church documents, particularly those concerning priestly formation.

Homosexuality as a Psychological Disorder

One of the clearest examples of this perspective is found in the 2005 Instruction from the Vatican’s Congregation for Catholic Education, which states that men with “deep-seated homosexual tendencies” should not be admitted to the priesthood. This document distinguishes between “transitory” same-sex attractions and a more ingrained homosexual orientation.2

The implication is clear: homosexuality is not a stable, natural minority variation but a symptom of deeper, unresolved psychological issues. The document reinforces this by using pathologizing language, describing deep-seated homosexual tendencies as “a situation that gravely hinders them from relating correctly to men and women.” Homosexuality, it suggests, is a form of emotional immaturity, an “adolescence not yet superseded.”3 Some men might be able to “recover” from their transitory same-sex attraction and be admitted to the priesthood, while others, whose homosexual tendencies are more permanent, must be excluded or dismissed from formation.

The Church’s pastoral and psychological approaches to homosexuality reinforce this assumption. Catholic counseling literature frequently presents heterosexuality as the natural outcome of a well-adjusted psychological development, emphasizing the importance of secure attachment to one’s same-sex parent and positive relationships with same-sex peers. If these developmental factors are missing or disrupted, the prevailing hypothesis suggests that homosexuality may emerge as a “maladaptive condition”,4 that is, a compensatory response to unmet emotional needs.

Courage, a Catholic apostolate to homosexual persons endorsed by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and the Holy See, reflects this typical approach. While it does not explicitly claim a singular cause for homosexuality, its official handbook acknowledges several commonly proposed explanations, including “an overbearing mother, or a physically or emotionally absent father, or a lack of interest or skill in sports or ‘gendered’ activities, or poor self-esteem.”5

An Outdated Model

These theories did not originate within Catholic thought. Instead, they draw heavily from early psychoanalytic models that viewed homosexuality as a failure of psychosexual development. Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), the founder of psychoanalysis, hypothesized that homosexuality arose from “arrested psychosexual development” caused by dysfunctional family dynamics. According to a 2016 report by the Southern Poverty Law Center:

“Freud’s ideas about the “triadic family” were developed to theorize that gay men were the product of families with an overbearing, dominant mother, a distant and weak father, and a sensitive child. The boy was said to thus fail to mature into a close relationship with his father, and ultimately to seek to replace that relationship by having sex with other men. A closely related theory blames early childhood trauma like sexual molestation. Today, the consensus of the vast majority of psychologists, psychiatrists and other counselors is that that model is entirely false.”6

Nonetheless, the hypothesis remains au courant in Catholic circles today. Psychological assessments required by the Church for prospective seminarians often focus on whether a man has developed a strong masculine identity through bonding with his father, male peers, and brothers. Dr. Peter Kleponis and Dr. Richard Fitzgibbons, two highly prominent Catholic psychologists, recommend that seminarians be required to provide “an in-depth history of secure attachment relationships with male peers, the father, and male siblings, if present, to evaluate the development of male confidence in childhood, adolescence, and young adult life.”7 This evaluation is explicitly recommended to filter out candidates with deep-seated homosexual tendencies: “The lack of secure, accepting, and positive relationships with male peers, the father, and a brother can result in weaknesses in male confidence, sadness, and anger, which are major unconscious factors in the development of same-sex attractions.”8

Fitzgibbons, who has served as a consultant for the Vatican’s Congregation for the Clergy, has long promoted theories that homosexuality in males can stem from external causal factors, not only the lack of secure attachment, but “poor body image; sex abuse trauma; mistrust in the mother relationship; severe betrayals by women, and narcissism.”9 Kleponis, for his part, frames homosexuality as one of a number of “deviant and dangerous forms of sexuality,” such as “bondage, bestiality, fetishes, and in some cultures sex with children.”10

Indeed, Fitzgibbons and Kleponis not only regard homosexuality as a psychological disorder but also suggest that its presence in the priesthood poses a moral and institutional risk to the Church. In the opening lines of their white paper, they stress that identifying candidates with deep-seated homosexual tendencies “is vitally important for the protection of minors and of the Church from further shame and sorrow,”11 implicitly linking homosexuality with sexual abuse.

Unfortunately, this negative framing extends beyond fringe psychological positions to the official language used by the Church to discuss homosexuality. In Church documents, same-sex attraction is rarely, if ever, spoken of in neutral terms. It is always paired with negative connotations: disorder, tendency, inclination, struggle, cross, trial.12 The concept of a gay identity is explicitly rejected. Homosexuality is not just “one way of being human”; it is a condition to be tolerated, but never affirmed.

Resistance to Scientific Research

Overall, this negative perspective on homosexuality often predisposes Catholics to reject scientific research on its etiology out of hand. Many Catholic pastoral materials—including those used in seminaries—downplay or dismiss findings from genetics, neurobiology, and developmental psychology, favoring instead the psychoanalytic idea that homosexuality is rooted in emotional conflicts or developmental deficits.

The claim that same-sex attraction has no biological foundation is frequently coupled with a deep suspicion toward those who identify as gay, as if acknowledging homosexuality as a stable sexual identity means capitulating to a secular ideology. Fitzgibbons and Kleponis take this suspicion a step further, treating a man’s belief in a biological basis for homosexuality as a predictor of his deep-seated homosexual tendencies:

“Those with deep-seated homosexual tendencies often identify themselves as ‘gay men’ which is based to a large extent upon their sexual attractions. They often reject the current scientific findings that there is no genetic or biological basis for SSA and believe they were born this way. They do not view homosexuality as a disordered inclination, are comfortable with their sexual attractions, subscribe to the increasingly prevalent belief that homosexuality is a normal variation in human sexuality, and think there is nothing wrong with homosexual acts. Their beliefs make them highly vulnerable to sexual acting out.”13

Fitzgibbons and Kleponis cite a 2008 American Psychological Association (APA) article as proof that “current scientific findings” rule out a genetic or biological basis for same-sex attraction. However, this is a blatant misrepresentation. The APA article does not state that homosexuality has no genetic or biological basis. Instead, it states that “no findings have emerged that permit scientists to conclude that sexual orientation is determined by any particular factor or factors.”14

In other words, the APA acknowledges that sexual orientation arises from a complex interplay of biological, genetic, and environmental factors, but does not dismiss a biological basis altogether. Fitzgibbons and Kleponis take scientific caution—an acknowledgment that no single “gay gene” has been identified—and twist it into an outright rejection of all biological factors. (It goes without saying that if Fitzgibbons and Kleponis can misuse the APA article in this way, it could just as easily be used to disprove their own hypothesis that sexual orientation is determined by psycho-pathological factors, trauma, or relational dynamics.)

The Theological Basis of Catholic Anthropology

The reason for Catholics’ widespread rejection of scientific research on the causes of homosexuality is, ultimately, theological. The Church’s entire sexual ethic is built on the premise that procreation is an intrinsic end, or purpose, of sexual relationships. Because same-sex couples cannot procreate, their relationships are, by definition, “disordered” and intrinsically evil.15 This assumption—that sexuality must be tied to reproduction in order to be morally good—prevents the Church from recognizing homosexuality as a natural part of human sexual diversity. Instead, it must be treated as a deviation from God’s plan, something that can never be fully accepted or integrated.

James Alison calls this the Church’s unexamined presupposition: the idea that all people are naturally heterosexual, that sex is intended only for procreation, and that any deviation from that must be a defect rather than a legitimate part of human diversity.16 The problem with this framework is that it assumes its conclusion from the start. It begins with the assumption that heterosexuality is the norm and then constructs explanations to justify this conclusion. The result is a circular logic that never allows for the possibility that homosexuality is simply a stable, naturally occurring variation in human sexuality.

But what if this fundamental assumption is wrong? What if homosexuality is not a deviation from the norm but a naturally occurring, stable variation in human sexuality? If that is the case, then the Church’s entire moral framework on homosexuality is built on a false premise. The next section will examine what the latest research actually tells us about the origins of same-sex attraction, and how the findings line up with the Church’s unexamined presuppositions.

What Science Actually Shows

As we have seen, Catholic pastoral and psychological literature assumes that homosexuality must have an external cause, such as childhood trauma, dysfunctional family dynamics, or poor self-esteem. This assumption remains deeply embedded in seminary formation and moral theology despite overwhelming scientific evidence to the contrary. Research in genetics, prenatal biology, neuroscience, and psychology confirms that homosexuality is neither chosen nor the result of social conditioning, but instead represents a naturally occurring, minority variation in human sexuality, arising from a complex interplay of genetic, neurobiological, and environmental factors that shape sexual orientation in a stable and enduring way.

The Genetic and Evolutionary Basis of Homosexuality

One of the strongest indicators that homosexuality has a biological foundation is its consistent heritability across populations. If same-sex attraction were purely a learned behavior—caused by relational dynamics or family dysfunction, for example—one would not expect to find such strong genetic correlations. However, research on identical (monozygotic) twins and fraternal (dizygotic) twins provides compelling evidence that genetics play a significant role in determining sexual orientation. A landmark study by Bailey and Pillard (1991) found that if one identical twin was gay, the likelihood of the other twin also being gay was approximately 52 percent, compared to 22 percent in fraternal twins and only 9 percent in adoptive brothers.17

More recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified specific loci on chromosomes 7, 8, and Xq28 that show statistically significant links to same-sex attraction.18 While no single “gay gene” has been identified, researchers widely agree that sexual orientation is polygenic, meaning it is influenced by multiple genes, each contributing a small but meaningful effect.

Critics might argue that if homosexuality has a biological basis, it should have been eliminated by natural selection. However, evolutionary models show that same-sex attraction persists precisely because of its genetic advantages: the same genes that contribute to male homosexuality enhance fertility in females,19 while homosexual individuals often play crucial roles in kin support, contributing to the survival of their extended family and increasing the overall reproductive support of their genetic relatives.20 Far from being an evolutionary dead-end, homosexuality has been consistently preserved in human populations across cultures and throughout human history.

Prenatal and Neurobiological Influences on Sexual Orientation

Beyond genetics, research has identified prenatal and neurobiological factors that contribute to the development of same-sex attraction. These studies indicate that homosexuality is shaped before birth, further undermining claims that it results from childhood trauma or social conditioning. One of the most consistent and well-replicated findings in sexual orientation research is the Fraternal Birth Order Effect (FBOE). Studies show that each additional older biological brother increases the likelihood of a male being gay by approximately 33 percent.21 The leading explanation for this effect is the maternal immune response theory: with each successive male pregnancy, the mother’s immune system produces antibodies against Y-linked proteins involved in male fetal brain development, subtly altering sexual differentiation in the brain.22 This effect is biological, not social, as it does not occur in adopted brothers or stepbrothers, confirming that the influence is prenatal rather than environmental.

Neuroscientific studies have further demonstrated that sexual orientation is associated with structural differences in the brain. Imaging studies have found that gay men and heterosexual women share similarities in brain structure and neural activation patterns, as do lesbians and heterosexual men.23 Differences have been identified in the anterior hypothalamus, a region linked to sexual behavior, as well as in the corpus callosum, which appears to be larger in gay men compared to their heterosexual counterparts.24 Additionally, research on pheromone processing has shown that gay men and heterosexual women exhibit similar neural responses when exposed to male pheromones, indicating that sexual attraction is deeply rooted in biological and neurological processes.25 These findings reinforce the conclusion that same-sex attraction is not a psychological dysfunction but a stable trait influenced by biological factors from an early stage of development.

Psychological and Developmental Factors: Addressing Common Misconceptions

Psychological research has thoroughly discredited the notion that homosexuality results from trauma, emotional dysfunction, or improper gender identity formation. Many studies have found that childhood gender nonconformity is correlated with adult sexual orientation, with 60 to 80 percent of gay men and 40 to 60 percent of lesbians recalling gender-nonconforming behavior in childhood.26 However, correlation does not imply causation. Rather than serving as evidence that homosexuality results from gender confusion, this correlation suggests that gender nonconformity is an early expression of an innate sexual orientation, not its cause.

One of the most frequently cited arguments against homosexuality within Catholic and other conservative circles is the claim that gay individuals experience higher rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality, implying that homosexuality is inherently linked to psychological distress. However, extensive research has shown that these mental health disparities are not caused by homosexuality itself, but by social rejection and discrimination. This is known as the Minority Stress Hypothesis, which posits that the mental health challenges faced by LGBTQ+ individuals stem from societal stigma, exclusion, and hostility rather than from their sexual orientation per se.27

Studies comparing LGBTQ+ individuals across different social environments confirm this hypothesis. Those living in supportive, affirming communities exhibit dramatically lower rates of mental health struggles compared to those in hostile or repressive settings.28 Unfortunately, the Church’s framing of homosexuality as “intrinsically disordered” contributes to this stress, reinforcing the very mental health disparities that it then cites as evidence of homosexuality’s dysfunctionality.

The Theological Challenge: Reconciling Science with Catholic Teaching

The scientific consensus on the biological and neurodevelopmental origins of homosexuality poses a serious challenge to the Church’s moral reasoning. If homosexuality is not the result of trauma, family dysfunction, or any other external cause, then the Church’s long-standing psychological explanations collapse.

Moreover, if homosexuality is a naturally occurring, minority variation in human sexuality, arising from a complex interplay of genetic, neurobiological, and environmental factors that shape sexual orientation in a stable and enduring way, then the Church’s insistence that it is “objectively disordered” becomes ethically and theologically untenable.

The Church’s Outdated Anthropology

A 1491 Map in a 1526 World

The Catholic Church’s teaching on homosexuality is built upon an anthropology that no longer holds up to scrutiny. For centuries, the Church has operated on the assumption that heterosexuality is not merely the statistical majority but the universal human norm, the “default setting” for all people, everywhere. This framework assumes that same-sex attraction is an anomaly that must be explained, either as a psychological disorder, a developmental failure, or a moral defect. But modern science has revealed a far more complex picture, one in which homosexuality is not an aberration but a stable, naturally occurring minority variation within human sexuality.

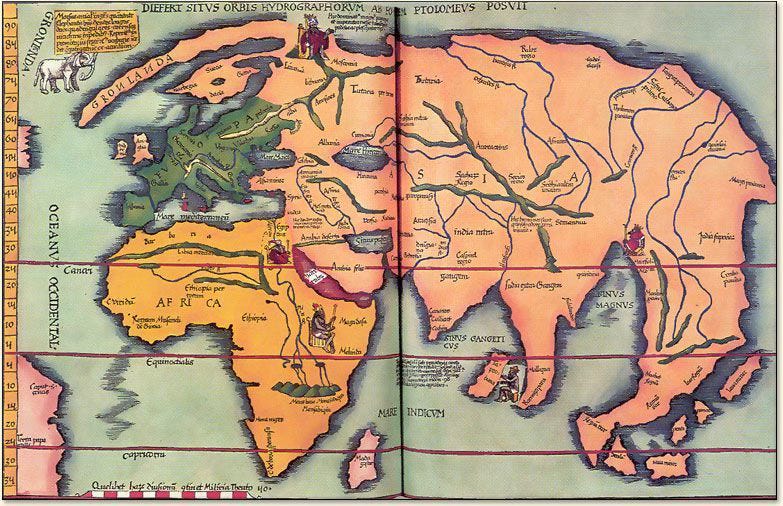

James Alison offers a compelling analogy for this epistemic shift. The Church’s anthropology, he argues, is like a map of the world in 1491. Before Columbus’s voyages, European cartographers assumed that between the westernmost reaches of Europe and the eastern shores of Asia lay nothing but uncharted waters filled with sea monsters. A map from that era, lacking knowledge of the Americas, was not wrong so much as incomplete—a reflection of what was knowable at the time. But by the year 1526, the situation had changed. Spanish explorers had mapped vast portions of the New World, and universities had been founded in Mexico City and Lima. In a 1526 world, a 1491 map was no longer just incomplete; it was dangerously misleading. A navigator relying on it would not only fail to reach his destination but would be more vulnerable to shipwreck than if he had never set sail at all.29

Alison applies this analogy to the Church’s doctrine on homosexuality. When the 1986 Letter to the Bishops on the Pastoral Care of Homosexual Persons declared same-sex attraction to be an “objective disorder,” it was articulating a worldview that would have been uncontroversial for most of human history. Much like a 1491 map, it reflected the limits of available knowledge. But to persist in using that framework today, when advances in genetics, neurobiology, and psychology have fundamentally altered our understanding of sexual orientation, is another matter entirely. As Alison puts it:

“An America-free map drawn up in 1526 … would have been something of a curiosity. It would be a sign either that someone hadn’t heard the news of what had happened in the intervening thirty-five years, or was so obstinate as to deny that it was really real, opting instead for a private reality.”30

The Church now faces the same dilemma. It can either acknowledge the reality that homosexuality is a stable, naturally occurring feature of human diversity, or it can cling to a theological model that rests on an outdated anthropology and circular reasoning. To insist that all people are naturally heterosexual—when overwhelming scientific evidence shows otherwise—is no longer a defensible moral position. It is a refusal to engage with the truth. And just as a 1526 navigator would be reckless to ignore the discovery of the Americas, the Church does not merely risk error in refusing to update its framework; it risks moral and intellectual irresponsibility.

Continuing to uphold outdated assumptions about homosexuality does not merely mean preserving a static doctrine. It actively harms real people. It perpetuates stigma, legitimizes discrimination, and fuels the very minority stress that scientific research has shown to be the root cause of mental health disparities among LGBTQ+ individuals.

Conclusion

At the heart of this challenge is the question of whether the Church is willing to let go of its outdated map and embrace a truer vision of the world. Theological development in this area would not be a capitulation to secular culture, but an act of intellectual and moral integrity. As we have seen in previous posts, the Church has, in the past, developed its doctrines in the light of new insights from philosophy and the sciences. Updating its anthropology of human sexuality would not be a break from tradition but a deepening of it, a recognition that truth unfolds over time and that the Spirit of Truth leads the Church into a fuller understanding of creation.

As Alison concludes his marvelous essay, in 1492, “the discovery of something new turned out to be a fulcrum in whose light a whole series of ways of knowing turned out to be insufficient to newly emerging tasks.”31 Recent scientific findings about the nature and origins of homosexuality are another fulcrum. The question now is whether the Church is willing to update its maps—or whether it will insist on navigating with a vision of the world that no longer exists.

Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed. (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1997), §2357.

Congregation for Catholic Education, Instruction Concerning the Criteria for the Discernment of Vocations with Regard to Persons with Homosexual Tendencies in View of Their Admission to the Seminary and to Holy Orders (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2005), §2.

Ibid.

Cf. Christopher Doyle, interview in Quacks: ‘Conversion Therapists,’ the Anti-LGBT Right, and the Demonization of Homosexuality, Southern Poverty Law Center, May 2016, 17. “I believe [homosexuality is] a maladaptive condition … Because of the lack of bonding and attachment with the same sex … the normal development does not occur.”

Courage International, Handbook for Courage and EnCourage Chaplains, 2020, 55.

Quacks, 7.

Peter C. Kleponis and Richard P. Fitzgibbons, “The Distinction Between Deep-Seated Homosexual Tendencies and Transitory Same-Sex Attractions in Candidates for Seminary and Religious Life,” Linacre Quarterly 78, no. 3 (August 2011): 358.

Ibid, 356.

Richard Fitzgibbons, e-mail message to James McTavish, May 23, 2015, quoted in James McTavish, “Spiritual Accompaniment for Persons with Same-Sex Attraction,” Linacre Quarterly 82, no. 4 (November 2015): 325.

Peter Kleponis, “Views on Healthy Sexuality: The World vs. The Church,” Those Catholic Men, January 29, 2018.

Kleponis and Fitzgibbons, “Distinction,” 356.

Cf. CCC §2357-2359. See also Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on the Pastoral Care of Homosexual Persons, October 1, 1986; Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Fiducia Supplicans (On the Pastoral Meaning of Blessings), December 18, 2023.

Kleponis and Fitzgibbons, “Distinction,” 356.

American Psychological Association, Answers to Your Questions: For a Better Understanding of Sexual Orientation & Homosexuality (Washington, D.C.: APA, 2008), 2.

Cf. CCC §2366, 2357.

James Alison, The Fulcrum of Discovery, or: How the “Gay Thing” Is Good News for the Catholic Church, James Alison Theology, 2009.

J. Michael Bailey and Richard C. Pillard, “A Genetic Study of Male Sexual Orientation,” Archives of General Psychiatry 48, no. 12 (1991): 1089–1096.

Andrea Ganna et al., “Large-Scale GWAS Reveals Insights into the Genetic Architecture of Same-Sex Sexual Behavior,” Science 365, no. 6456 (2019): 882-885.

Andrea Camperio Ciani et al., “Sexually Antagonistic Selection in Human Male Homosexuality,” PLoS ONE 3, no. 6 (2008): e2282.

Paul L. Vasey and Doug P. VanderLaan, “Birth Order and Male Androphilia in Samoan Fa’afafine,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 39, no. 1 (2010): 192–197.

Anthony F. Bogaert, “Biological versus Nonbiological Older Brothers and Men’s Sexual Orientation,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, no. 28 (2006): 10771–10774.

Anthony F. Bogaert et al., “Male Homosexuality and Maternal Immune Responsivity to the Y-Linked Protein NLGN4Y,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, no. 2 (2018): 302–306.

Ivanka Savic and Per Lindström, “PET and MRI Show Differences in Cerebral Asymmetry and Functional Connectivity Between Homo- and Heterosexual Subjects,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105, no. 27 (2008): 9403–9408.

Simon LeVay, “A Difference in Hypothalamic Structure Between Heterosexual and Homosexual Men,” Science 253, no. 5023 (1991): 1034–1037.

Minming Zhang et al., “Neural circuits of disgust induced by sexual stimuli in homosexual and heterosexual men: An fMRI study,” European Journal of Radiology 80, no. 2 (2011): 418-425.

Gerulf Rieger et al, “Sexual Orientation and Childhood Gender Nonconformity: Evidence from Home Videos,” Developmental Psychology 44, no. 1 (2008): 46–58.

Ilan H. Meyer, “Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence,” Psychological Bulletin 129, no. 5 (2003): 674–697.

Mark L. Hatzenbuehler, “How Does Sexual Minority Stigma ‘Get Under the Skin’? A Psychological Mediation Framework,” Psychological Bulletin 135, no. 5 (2009): 707–730.

Alison, The Fulcrum of Discovery.

Ibid.

Ibid.